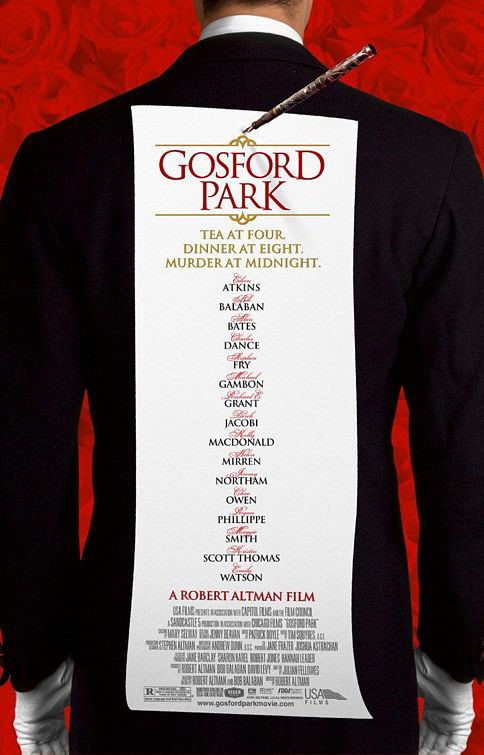

Gosford Park [2001]

Please join us for a special screening of Robert Altman’s Gosford Park [2001].

- Screening Date: Thursday, December 1st, 2016 | 7:00pm

- Venue: Dipson Theatres Amherst

- Specifications: 2001 / 131 minutes / English / Color

- Director(s): Robert Altman

- Print: Supplied by Focus Features

- Tickets: $9.50 general admission at the door

Event Sponsors:

Venue Information:

3500 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14226

Synopsis

Courtesy of USA Films press kit:

Robert Altman, one of America’s most distinctive filmmakers, journeys to England for the first time to create a unique film mosaic with an outstanding ensemble cast.

It is November, 1932. Gosford Park is the magnificent country estate to which Sir William McCordle and his wife, Lady Sylvia, gather relations and friends for a shooting party. They have invited an eclectic group including a countess, a World War I hero, the British matinee idol Ivor Novello and an American film producer who makes Charlie Chan movies. As the guests assemble in the gilded drawing rooms above, their personal maids and valets swell the ranks of the house servants in the teeming kitchens and corridors below-stairs.

But all is not as it seems: neither amongst the bejewelled guests lunching and dining at their considerable leisure, nor in the attic bedrooms and stark work stations where the servants labor for the comfort of their employers. Part comedy of manners and part mystery, the film is finally a moving portrait of events that bridge generations, class, sex, tragic personal history — and culminate in a murder. (Or is it two murders … ?)

Ultimately revealing the intricate relations of the above and below-stairs worlds with great clarity, Gosford Park illuminates a society and way of life quickly coming to an end.

Tidbits:

- Berlin International Film Festival – 2002

- Academy Awards – 2002 – Winner: Best Writing, Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen

- Academy Awards – 2002 – Nominee: Best Picture, Best Actress in a Supporting Role, Best Actress in a Supporting Role, Best Director, Best Art Direction-Set Decoration & Best Costume Design

- Writers Guild of America – 2002 – Winner: Best Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen (Screen)

- Screen Actors Guild Awards – 2002 – Winner: Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Supporting Role & Outstanding Performance by the Cast of a Theatrical Motion Picture

- Golden Globes – 2002 – Winner: Best Director – Motion Picture

- Golden Globes – 2002 – Nominee: Best Motion Picture – Comedy or Musical, Best Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role in a Motion Picture, Best Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role in a Motion Picture & Best Screenplay – Motion Picture

Gerald Peary Interview

Courtesy of geraldpeary.com:

The Museum of Fine Arts program promised only brief words from filmmaker Robert Altman, 76, when he appeared last month for a sneak of Gosford Park, his murder mystery with an all-star British cast set at a palatial English estate before World War II. But Altman was so revved up by the screening, that he spoke long into the night:

“I refer to this film as Ten Little Indians meets Rules of the Game. Except for two American actors, it’s an English film. The cast were on the set all the time, people like Alan Bates, who didn’t have a thing to say in most scenes and was in the background. They were all paid the same thing. They accepted the deal or they didn’t. They’re used to acting in ensembles. Nobody wanted to misbehave. Even Maggie Smith, who has a funny reputation, was delightful. I can’t imagine that of an American cast today.

“A period piece like this usually is so proper, everyone talks so carefully, every shot is so precise. I went back to a style of twenty-five years ago of The Long Goodbye, in which I used cameras almost always in motion, moving arbitrarily. Audiences are trained too much by television, where you can get a beer and come back and nothing has changed. I want an audience that’s alert. The British accents? You don’t have to understand all the words, unless you are one of those people sitting with a TV dinner who needs to know everything.

“Bob Balaban came to me two-and-a-half years ago and asked if there was something we could develop together. I said, ‘I’ve never done a who-done-it. People come to an English house for the weekend.’ Some who watch the movie say, ‘I knew from the beginning who did it. You didn’t hide it very well.’ I say,’If you figured it out, that’s OK. I wasn’t trying to make a mystery.’ We’re not going to sit around for 2 1/2 hours to discover the plot, I’m bored with plots. And I’m not interested that anyone pay for the crime. That’s not what I care about. Less than 50% of murderers in the world are caught. What purpose would it serve?”

“I haven’t seen Rules of the Game for twenty years but it did inspire me [with the upstairs people and the below-stairs people.] Julian Fellowes, the screenwriter, is one of those upstairs people. His wife is a Lady-in-Waiting for the Countess of Kent. He was on the set all the time, tapping on my shoulder. As an American in England, I wanted it right. The social structure of below-stairs people is more complicated and structured that upstairs people, who don’t know any different than their behavior. The maid will be in the room, and they pay no notice. It could be a dog.”

The next morning at his hotel, Altman was just as talkative and immensely affable, but maybe he’d OD’d on the tea-and-crumpets milieu of Gosford Park. For a time, we had coffee and talked sports, about the dismaying collapse of the Sox. Said Altman, “In August, I thought they’re going to make it this year. I’m a Red Sox fan, and they are the only team I root for.” But what about being a native of Kansas City? “I always thought the Royals were flat.”

OK, Gosford Park. I wondered if he had any special affection for the old-fashioned detective genre. “No, I just have to have a point of view, a reference. It’s a classic situation: all suspects under one roof. I’ve never read Agatha Christie. Her Ten Little Indians? I don’t think so. The Hardy Boys? I didn’t read that kind of book. As a kid I read Spengler’s Decline of the West. I saw Sherlock Holmes in the movies. I don’t know if I could read it. But the genre has been copied, xeroxed, reprinted many ways. You dig out the information in your brain.”

His filmic research for the movie? “I watched the 1934 film, Charlie Chan in London, made for about $12, in which there isn’t one shot of London but there’s a country home with stables, a butler, a groom. We ran it, I didn’t get anything out of it. Still, there’s always the bumbling inspector like in Chan movies. I tried to set up a Charlie Chan parallel with Stephen Fry’s Inspector Thompson.”

I mentioned that Thompson moves about like Monsieur Hulot, the comic creation of France’s Jacques Tati. “You got it!” Altman responded happily. “You and Paul Thomas Anderson are the only ones. I just love Tati’s works. They are subtle but broad. Broadly subtle.”

The name of the movie? “Julian’s original title was The Other Side of the Tapestry. I thought that was awkward. He started looking through books and came up with Gosford Park. Nobody liked it, everyone fought me on it. But when you make a picture using a name, that’s its name. It’s not a gripping title. But then M*A*S*H wasn’t either.”

Director Bio

“Filmmaking is a chance to live many lifetimes.”

Courtesy of The Criterion Collection:

Few directors in recent American film history have gone through as many career ups and downs as Robert Altman did. Following years of television work, the rambunctious midwesterner set out on his own as a feature film director in the late 1950s, but didn’t find his first major success until 1970, with the antiauthoritarian war comedy M*A*S*H. Hoping for another hit just like it, studios hired him in the years that followed, most often receiving difficult, caustic, and subversive revisionist genre films. After the success of 1975’s panoramic American satire Nashville, Altman once again delved into projects that were more challenging, especially the astonishing, complex, Bergman-influenced 3 Women. Thereafter, Altman was out of Hollywood’s good graces, though in the eighties, a decade widely considered his fallow period, he came through with the inventive theater-to-film Nixon monologue Secret Honor and the TV miniseries political satire Tanner ’88. The double punch of The Player and the hugely influential ensemble piece Short Cuts brought him back into the spotlight, and he continued to be prolific in his output into 2006, when his last film, A Prairie Home Companion, was released months before his death at the age of eighty-one.

Filmography:

- A Prairie Home Companion (2006)

- The Company (2003)

- Gosford Park (2001)

- Dr. T and the Women (2000)

- Cookie’s Fortune (1999)

- The Gingerbread Man (1998)

- Kansas City (1996)

- Ready to Wear (1994)

- Short Cuts (1993)

- The Player (1992)

- Vincent & Theo (1990)

- The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (1988)

- Aria (1988)

- O.C. And Stiggs (1987)

- Beyond Therapy (1987)

- Fool For Love (1985)

- Secret Honor (1984)

- Streamers (1983)

- Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982)

- Popeye (1980)

- Health (1980)

- A Perfect Couple (1979)

- Quintet (1979)

- A Wedding (1978)

- 3 Women (1977)

- Nashville (1975)

- Thieves Like Us (1974)

- California Split (1974)

- The Long Goodbye (1973)

- images (1972)

- McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

- M*A*S*H (1970)

- Brewster McCloud (1970)

- That Cold Day in the Park (1969)

- Countdown (1968)

- The James Dean Story (1957)

- The Delinquents (1957)

Links

Here is a curated selection of links shared on our Facebook page for additional insight/information:

- 10/29/16 – Need a beginner’s guide to the work of Robert Altman? Look no further than Noel Murray’s in-depth intro over at The A.V. Club! – link

- 10/30/16 – “The undeniable brilliance of Altman’s cinema is most closely tied to a simple point made in each of his greatest works: the tapestry of overlapping lives is richer than overproduced spectacle. Witness Nashville, The Player, Short Cuts, or Gosford Park: each film lets characters complicate events by their unique personality traits rather than showcases special-effects technicians and pyrotechnics.” Garrett Chaffin-Quiray (501 Movie Directors, 2007) – link

- 11/01/16 – “Robert Altman was one of the boldest, most versatile filmmakers of the late 20th century. He’s influenced generations of directors with his warm portraits of humanity in flux, his deft handling of ensemble casts and willingness to experiment with sound, storytelling and subject matter.” Owen Williams & Phil De Semlyen, Empire Magazine – link

- 11/14/16 – “Twelve years after the release of Gosford Park—one of director Robert Altman’s biggest hits—the film seems more relevant than ever, both for how it fits into Altman’s filmography and for how it presages one of today’s most popular TV series. Screenwriter Julian Fellowes won an Academy Award for Gosford Park, and would go on to create the wildly successful and very similar BBC drama ‘Downton Abbey’.” Noel Murray, The Dissolve – link

- 11/22/16 – On Friday (11/25/16), in honor of the 10th anniversary of his death, the BFI published Geoff Andrew’s must read intro to the wild and woolly world of director Robert Altman. – link

- 11/27/16 – “Gosford Park is the kind of generous, sardonic, deeply layered movie that Altman has made his own. As a director he has never been willing to settle for plot; he is much more interested in character and situation, and likes to assemble unusual people in peculiar situations and stir the pot. Here he is, like Prospero, serenely the master of his art.” Roger Ebert – link

- 11/28/16 – “Critical consensus about any movie is impossible, but judging from end-of-the-year polls, Gosford Park by Robert Altman is widely recognized as a masterpiece.” Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chicago Reader – link

- 11/29/16 – Must read for Robert Altman fans – Stephen Lemons’ gushing career overview for Salon – link