Lilies of the Field [1963]

Please join Cultivate Cinema Circle as we screen six films starring the late, great Sidney Poitier. Last up is Ralph Nelson’s Oscar-winning (Best Actor in a Leading Role) film Lilies of the Field [1963].

- Screening Date: Saturday, June 18th, 2022 | 1:00pm

- Venue: The Mason O. Damon Auditorium at Buffalo Central Library

- Specifications: 1963 / 94 minutes / English / Black & White

- Director(s): Ralph Nelson

- Print: Supplied by Swank

- Tickets: Free and Open to the Public

Event Sponsors:

Venue Information:

Downtown Central Library Auditorium

1 Lafayette Square, Buffalo, NY 14203

(Enter from Clinton Street between Oak and Washington Streets)

716-858-8900 • www.BuffaloLib.org

COVID protocol will be followed.

Synopsis

An ex-GI builds a chapel for a desert convent, becoming the answer to the mother superior’s prayers while endearing himself to the local townspeople and avoiding an arrest for a previous crime.

Tidbits:

- Berlin International Film Festival – 1963 – Winner: Best Actor (Silver Berlin Bear), Honorable Mention: Best Feature Film Suitable for Young People (Youth Film Award), Winner: Interfilm Award & Winner: OCIC Award

- Academy Awards – 1964 – Nominee: Best Cinematography (Black-and-White), Best Picture, Best Actress in a Supporting Role & Best Writing (Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium)

- Academy Awards – 1964 – Winner: Best Actor in a Leading Role

- National Board of Review – 1963 – Winner: Top Ten Films

- BAFTA Awards – 1965 – Nominee: Best Foreign Actor & UN Award

- Directors Guild of America – 1964 – Nominee: Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures

- Writers Guild of America – 1964 – Winner: Best Written American Comedy (Screen)

- Golden Globes (USA) – 1964 – Nominee: Best Motion Picture – Drama & Best Supporting Actress

- Golden Globes (USA) – 1964 – Winner: Best Actor – Drama & Best Film Promoting International Understanding

Actor Bio

“I never had an occasion to question color, therefore, I only saw myself as what I was… a human being.”

Courtesy of TCM:

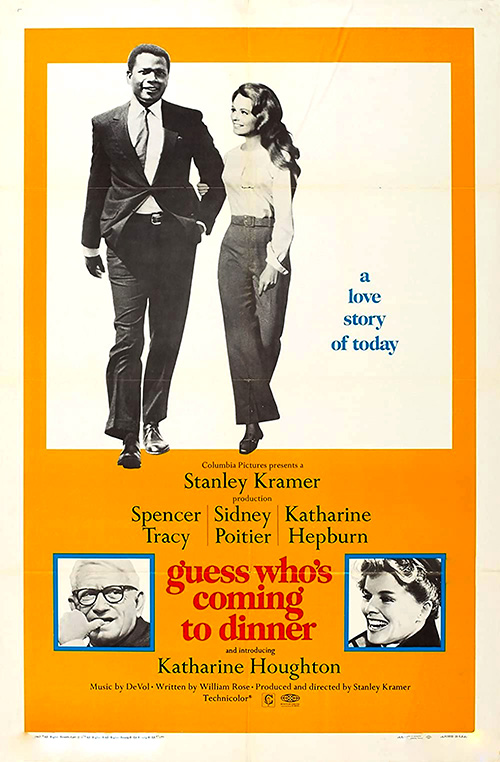

“Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?” returned Poitier to the familiar turf of “Negro problem” pictures, but with a contemporized twist: instead of battling the unabashed ignorance of racist America, he found himself opposite sophisticated Northerners played by Katherine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy (in his last film). The grand old screen duo played an ostensibly enlightened couple who find their liberal sensibilities strained when their daughter brings home her fiancé, an older, divorced doctor, who just happens to be Poitier. Again under Kramer’s direction, the picture parlayed the myriad pitfalls of the stark realities simple “love” still faced, given the country’s darkly drawn racial lines, especially at the zenith of the civil rights movement; the Supreme Court had just that summer struck down 14 Southern states’ standing laws against interracial marriages, and Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated while the film was still in theaters. The film’s heady discourse struck a chord, taking in a for-the-time whopping $56.7 million at the box office in North America.

But Poitier’s most dauntlessly cool performance came in “In the Heat of the Night,” a steamy neo-noir that set Poitier in the heart of the deep South – still so blatantly segregated that Poitier nixed location shooting in Mississippi, prompting the production to move to tiny Sparta, IL. Poitier played a Philadelphia homicide detective, Virgil Tibbs, initially accused of a murder in a hick Mississippi town, who then assists the local Sheriff Gillespie (Rod Steiger) solve the case. Under the deft direction of Norman Jewison, Poitier and Steiger played a dueling character study; a sophisticated black authority the likes of which the town has never seen versus an abrasive, outwardly racist yokel stereotype more enlightened and thoughtful than he lets on. The film also proved a hit, winning Oscars for Best Picture and Best Actor (Steiger).

Poitier’s three films in 1967 made him, by total box-office receipts, the No. 1 box-office draw in Hollywood. And yet, even in the thick of his success, Poitier’s singular identification as the spokesman for African-Americans came with proportionate scrutiny. While he had embraced the civil rights movement publicly – he keynoted the annual convention of Martin Luther King’s activist Southern Christian Leadership Conference in August 1967 – some in the African-American community (as well as some film critics) began vocalizing their displeasure with the never-ending string of saintly and sexless characters Poitier played. Black playwright and drama critic Clifford Mason became the sounding board for these sentiments in an analysis published on the front page of The New York Times’ drama section on Sept. 10, 1967. Mason referred to Poitier’s characters as “unreal” and essentially “the same role, the antiseptic, one-dimensional hero.”

Although devastated by the attacks, Poitier himself had begun to chafe against the cultural restrictions which cast him as the unimpeachable role model instead of a fully flawed and functioning human. Sidney Poitier attempted to take a greater hand in his work, penning a romantic comedy that he would star in called “For the Love of Ivy” (1968), and attempting a more visceral representation of the travails of inner city America in “The Lost Man” (1969), but neither met the success of his previous films or effectively muted his critics. The Times’ Vincent Canby called the latter, “Poitier’s attempt to recognize the existence and root causes of black militancy without making anyone – white or black – feel too guilty or hopeless.” He also founded a creator-controlled studio, First Artists Corp., with partners Paul Newman and Barbra Streisand. But his damaged image, amid an up-and-coming crop of black actors unencumbered by his “integrationist” stigma, enforced a sense of isolation about Poitier, likely amplified by a falling out with his longtime friend Belafonte and his estrangement from wife Juanita.

Some of that oddly went reflected in an unlikely, blaxploitation-infused sequel, “They Call Me MISTER Tibbs!” (1970), in which he reprised his classic character to ill-effect. By 1970, Poitier had struck up a passionate new romance with Canadian model Joanna Shimkus and exiled himself to a semi-permanent residence in The Bahamas. He would make one more forgettable Tibbs sequel, “The Organization” (1971), but he would return to Hollywood in a different capacity.

With Hollywood now recognizing the power of the black purse, even for cheaply produced “blaxploitation” pictures, Columbia saw the potential for “Buck and the Preacher” (1972), in which Harry Belafonte and Poitier would play mismatched Western adventurers who team up to save homesteading former slaves from cowboy predators. Belafonte co-produced and Poitier, after initial squabbles with the director, was given reign and Poitier, after initial squabbles with the director, was given reign by the studio to complete the film in the director’s chair.

He produced, directed and starred in his next outing, a tepid romance called “A Warm December” (1973), which tanked, but he found his stride soon after back among friends. He directed and starred with Belafonte, Bill Cosby and an up-and-coming Richard Pryor in their answer to the blaxploitation wave, “Uptown Saturday Night” (1974), an action/comedy romp about two regular guys (Cosby and Poitier) whose devil-may-care night out becomes an odyssey through the criminal underworld. “Uptown” proved such a winning combo that Poitier would make two more successful buddy pictures starring himself and Cosby: “Let’s Do it Again” (1975) and “A Piece of the Action” (1977).

Poitier also returned to Africa and an actor-only capacity for another anti-apartheid film, “The Wilby Conspiracy” (1975), co-starring Michael Caine. After marrying Shimkus in 1976, he returned to the States most notably to direct Pryor’s own buddy picture; the second comedy pairing Pryor with Gene Wilder, “Stir Crazy” (1980), a story about two errant New Yorkers framed for a crime in the west and imprisoned. With Poitier letting the two actors’ fish-out-of-water comic talents play off their austere environs, the film became one of highest-grossing comedies of all time. A later outing with Wilder, “Hanky Panky” (1982), and a last directorial turn with Cosby, the infamous flop “Ghost Dad” (1990), proved profoundly less successful.

After more than a decade absent from the screen, Poitier made a celebrated return as an actor in the 1988 action flick “Shoot to Kill” and the espionage thriller “Little Nikita” (1988), though both proved less than worthy of the milestone. He would take parts rarely after that; only those close to his heart in big-budget TV movie events: NAACP lawyer -later the U.S.’s first African-American Supreme Court justice – Thurgood Marshall in “Separate But Equal” (ABC, 1991), Nelson Mandela, the heroic South African dissident and later president, in “Nelson & De Klerk” (Showtime, 1997), and “To Sir, With Love II” (CBS, 1996). He also took some choice supporting roles in feature actioners “Sneakers” (1992) and “The Jackal” (1997).

In 1997, the Bahamas appointed Poitier its ambassador to Japan, and has also made him a representative to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. In 1999, the American Film Institute ranked Poitier No. 22 in the top 25 male screen legends, and in 2006, the AFI’s list of the “100 Most Inspiring Movies of All Time” tabulated more Poitier films than those of any other actor except Gary Cooper (both had five). In 2002, he was given an Honorary Oscar with the inscription, “To Sidney Poitier in recognition of his remarkable accomplishments as an artist and as a human being,” and in 2009, President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. trade, accepts one teaching marginal, troubled cockney students in London and reached them via honest empathy and by treating them as adults. Buoyed by the popular title song by Brit-pop star Lulu (who also played a student), the film became a sleeper hit.

Filmography:

- Moms Mabley: I Got Somethin’ to Tell You (2013)

- Sing Your Song (2011)

- Tell Them Who You Are (2004)

- The Last Brickmaker in America (2001)

- The Simple Life of Noah Dearborn (1999)

- Free of Eden (1999)

- David and Lisa (1998)

- Mandela and de Klerk (1997)

- The Jackal (1997)

- To Sir With Love II (1996)

- Wild Bill: Hollywood Maverick (1995)

- A Century Of Cinema (1994)

- World Beat (1993)

- Sneakers (1992)

- Shoot To Kill (1988)

- Little Nikita (1988)

- The Spencer Tracy Legacy (1986)

- A Piece Of The Action (1977)

- The Wilby Conspiracy (1975)

- Let’s Do It Again (1975)

- Uptown Saturday Night (1974)

- Buck and the Preacher (1972)

- A Warm December (1972)

- Brother John (1971)

- The Organization (1971)

- King: A Filmed Record … Montgomery to Memphis (1970)

- They Call Me MISTER Tibbs (1970)

- The Lost Man (1969)

- For Love of Ivy (1968)

- To Sir, With Love (1967)

- Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967)

- In the Heat of the Night (1967)

- Duel at Diablo (1966)

- A Patch of Blue (1965)

- The Slender Thread (1965)

- The Bedford Incident (1965)

- The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965)

- The Long Ships (1964)

- Lilies of the Field (1963)

- Pressure Point (1962)

- A Raisin in the Sun (1961)

- Paris Blues (1961)

- All the Young Men (1960)

- Virgin Island (1960)

- Porgy and Bess (1959)

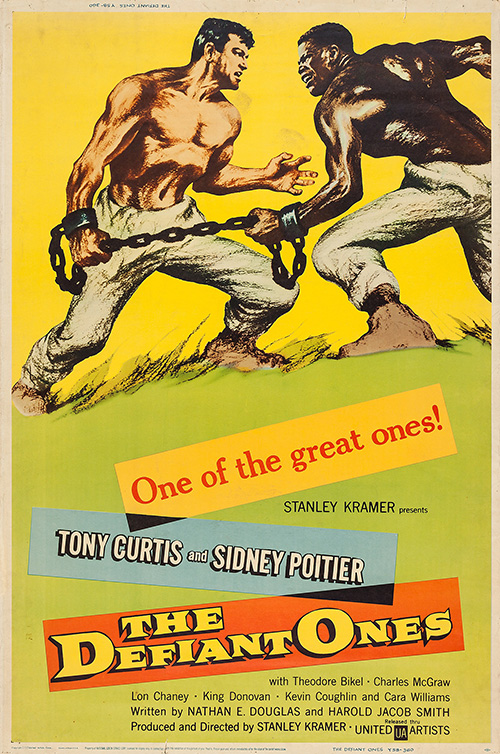

- The Defiant Ones (1958)

- The Mark of the Hawk (1958)

- Edge of the City (1957)

- Band of Angels (1957)

- Something of Value (1957)

- Good-Bye, My Lady (1956)

- Blackboard Jungle (1955)

- Go Man Go (1954)

- Red Ball Express (1952)

- Cry, the Beloved Country (1952)

- No Way Out (1950)

Director Bio

Courtesy of TCM:

Theater actor and director who began working in TV in the 1950s and made his feature debut with “Requiem for a Heavyweight” (1962), the film version of a Rod Serling teleplay he had previously directed. Divorced from actress Celeste Holm.

Filmography:

- You Can’t Go Home Again (1979)

- Christmas Lilies of the Field (1979)

- Lady of the House (1978)

- A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But A Sandwich (1977)

- Embryo (1976)

- The Wilby Conspiracy (1975)

- The Wrath of God (1972)

- Flight of the Doves (1971)

- Soldier Blue (1970)

- …tick…tick…tick… (1970)

- Counterpoint (1968)

- Charly (1968)

- Duel at Diablo (1966)

- Once a Thief (1965)

- Fate Is the Hunter (1964)

- Father Goose (1964)

- Soldier in the Rain (1963)

- Lilies of the Field (1963)

- Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962)

Links

Here is a curated selection of links for additional insight/information:

- Cultivate Cinema Circle info-sheet – link

- “It’s impossible now to assess the influence of positive discrimination in making Poitier the first black man to win the Oscar for Best Actor, but against competition from Albert Finney, Richard Harris and Paul Newman, his essentially lightweight performance as the handyman building a new chapel for a group of German nuns hardly seems, in hindsight, a front runner. Hard to begrudge him the plaudits, of course, but this gentle liberal offering from the Civil Rights era is too busy being audience friendly to count for much. Racial issues are the background, given the character’s rootless fortunes, and there’s a hint of tension with the construction company foreman (director Nelson, uncredited), but for the most part Poitier is all hard-working decency and will-to-succeed personified. Skala’s steely Mother Superior thankfully seasons the feelgoodery, but the other sisters contribute twee comedic misunderstandings and back-up chorus to Poitier’s thuddingly symbolic hot gospelling. It might be significant as an early independent movie made good, but Poitier got better when he got angrier for In the Heat of the Night four years later.” – Trevor Johnston, Time Out [2012] – link

- “Lilies of the Field is a funny, sentimental, charming and uplifting film, in which intelligence, imagination and energy are proved again to be beyond the price of any super-budget. The United Artists release, produced and directed by Ralph Nelson, could be termed the sleeper of the year if it had not already grabbed a handful of prizes at the Berlin Film Festival. So it comes not unheralded. None the less, festival awards do not always indicate popular appeal. Lilies, it is safe to say, will be a great audience picture. It deserves all its popularity and whatever artistic success it is granted….Sidney Poitier plays the young Negro who wanders by chance into the small religious community somewhere in the desert Southwest. The nuns have inherited the arid property and are trying to make it a useful addition to the impoverished community, hopefully planning a church, a school, a hospital. It is apparent to the Mother Superior that Poitier is an instrument of the Lord in this plan. It is not so quickly apparent to Poitier…Although Poitier is a Negro, and plays a Negro, the role is not that of any Negro stereotype, however well intentioned. The character is a universal young man, today’s young man, hep, flip and yet with a longing to create, to build something of enduring value in a world where the bulldozer seems designed to level impartially hill and home. Poitier has had little opportunity to display his comic talents. He shows here his timing and technique are impeccable. His relationship with the five women is delicate — not because of difference in race but of sex — and plays beautifully.” – James Powers, The Hollywood Reporter [1963] – link